Why Voting Matters? Through the Lens of a 95-year-old Black Woman

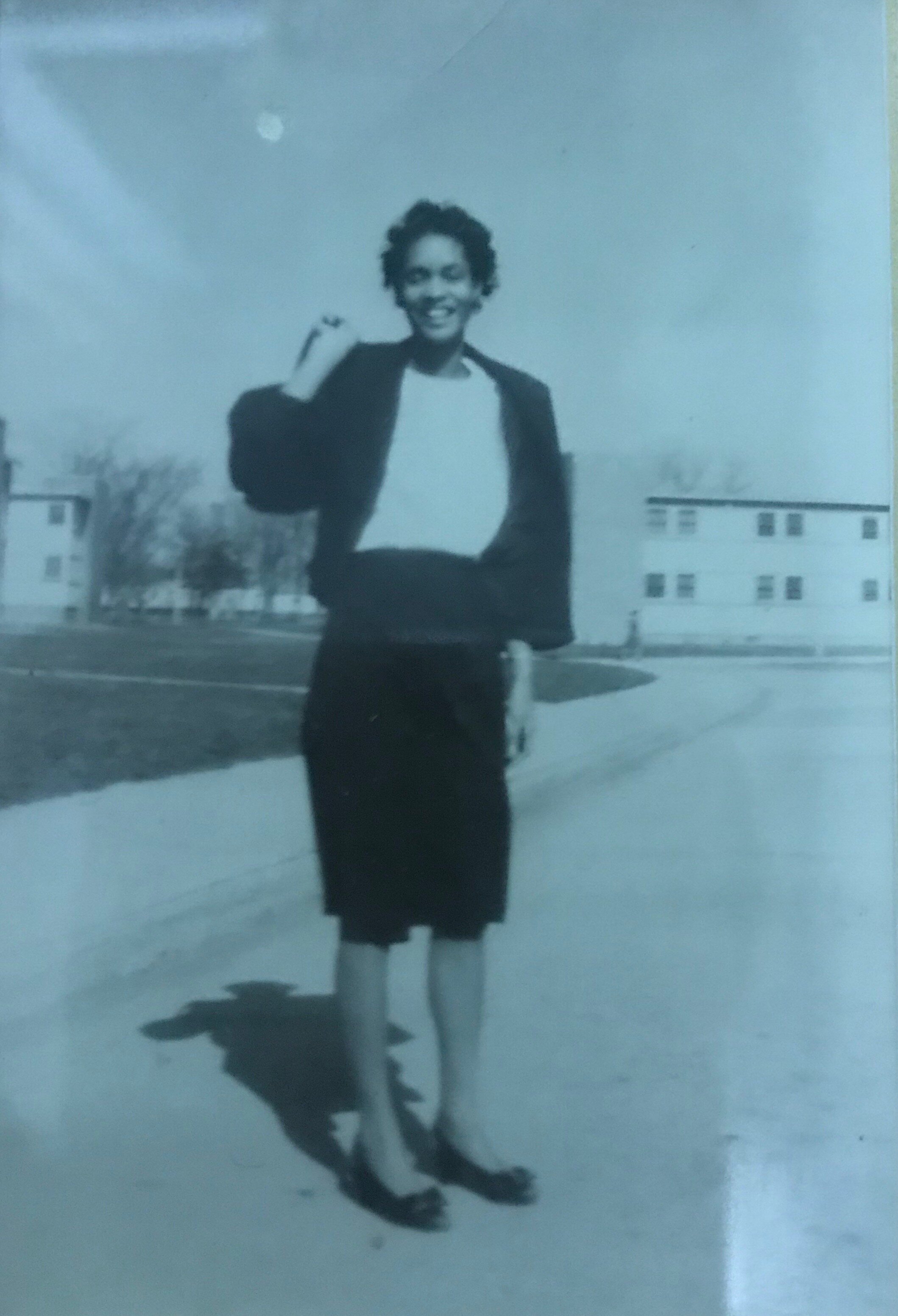

Florence E. Adams was born August 10th, 1923 in Trenton, New Jersey. 93 years later, I pushed her, my grandmother, through the newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. Different people stopped to look at her with a look of awe in their eyes. As she was witnessing her history, we were all witnesses to her.In 1946, after World War II, she left New Jersey for the Nation’s capital, where she worked as a secretary in the Adjutant General’s Office at the Pentagon. Leaving that position a few years later, she went on to attend American University, earning a degree in education, and then later a Master’s Degree from Federal City College, presently named the University of the District of Columbia.As I pushed her up the final ramp of the museum, there loomed in front of us a large but intimate photo of President Obama and his family, at Grant Park in Chicago, celebrating his presidential victory in 2008. My grandmother pulled a Kleenex out from her pocketbook to wipe away the small tear that streamed down her soft, brown cheek.“For a black person, especially a black woman, we were so proud that at last something so magnificent had happened, something we thought we’d never see,” my grandmother uttered softly. She was 42-years-old when young president JFK was tragically assassinated, after which President Lyndon B. Johnson became president. In November of 1963, he passed the 15thamendment aimed at eroding the legal barriers at the state and local levels aimed at preventing African Americans from exercising their right to vote.“There were always extra rules for blacks compared to their white counterparts. Whites kept blacks from voting, especially down south.”“Do you remember the first time you voted?” I inquired of her.“I don’t, but I remember it was at J.C. Nalle Elementary in Southeast Washington D.C., where your mother and aunt attended grade school. Back then there was one place, two if you were lucky, where you could vote. Everyone would be standing at one pole, lines wrapped around the block. It was not as simple as it is today. There is no excuse today for not voting; you can mail it in. All you have to do is fill out the form and put it back in the mail.”As she continued, she expanded on the history of blacks and voting. “My mother always voted once she was allowed. She voted Republican as many blacks, at that time, did because of [Lincoln]; he freed the slaves, thus, blacks voted republican.”Without knowing history and its context, one cannot properly act in the present. If anyone asked me where I was when I first voted, although the polling station escapes me now, I could tell you that it was in Atlanta, Georgia, when I was a freshman student at Emory University. I believe that knowing the exact location of one’s first vote is a vociferous and commanding testament to the historic achievement of the black vote. Over the course of my grandmother’s life, she is one of few who have been in both the “have nots” and the “haves” reminding us, as African-Americans that, too often, we forget that although we now can, we once could not. To vote is simultaneously a gift, a right, and a duty. This amnesia that can cause people to do otherwise is both dangerous and debilitating.As she looked me in the eye before we left the museum, she said, “You can’t be too tired to vote. Not now, not ever. You have to vote for the people who will do right by you.”And so, we must.